Scotty Campbell was that rare academic who could move seamlessly in and out of the public sector throughout a long and distinguished career. I discuss Campbell’s life and work in my forthcoming book, Public Service Exemplars: “A Finer Spirit of Hope and Achievement.”

During his time in academe, Campbell was hailed as the creator and director of the Metropolitan Studies program at the Maxwell School at Syracuse University. He directed the program from 1961 until 1969. He became dean of the school in 1969 and served for seven years. In his heyday during the 1960s and 1970s, Campbell influenced generations of students and colleagues. He eventually left to serve as dean of the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas in Austin.

His government service included assignments at the Civil Service Commission (CSC) as well as the Office of Personnel Management (OPM). During his tenure at the CSC, he was instrumental in lobbying for President Jimmy Carter’s civil service reforms. After the civil service laws were modernized, Campbell became the first OPM director, where he helped to establish norms and procedures for the new agency. In all his endeavors, “Scotty” was remembered as the consummate professional, dedicated to his cause, and always collegial. He received numerous accolades and awards throughout his long career.

Alan Keith "Scotty" Campbell was born in Elgin, Nebraska, on May 31, 1923, and attended Whitman College, a small liberal arts institution in Walla Walla, Washington. He graduated in 1947. Later, he earned a Master of Public Administration degree at Wayne University (now Wayne State University) in Detroit, Michigan, and a Ph.D. from Harvard University. He was briefly a research scholar at the London School of Economics during the early 1950s.

Campbell initially pursued an academic career, serving as a teaching fellow and assistant director of the summer school program at Harvard from 1950 until 1955. Afterward, he moved on to Hofstra University, a private institution of higher learning in Hempstead, New York. Campbell was a professor and chair of the political science department at Hofstra from 1955 until 1960. He moved to the Maxwell School in 1961, where he became a nationally prominent academic.

At a time when many of his peers churned out turgid, impenetrable prose filled with jargon, Campbell’s academic writing was distinguished by its quality and clarity. He strongly believed that academic research should have practical applications, and he strove to reach a large audience. He always sought to write for policymakers as well as academics.

Campbell’s early work focused on the plight of inner cities in the United States. As residents abandoned cities in favor of the suburbs during the 1950s and 1960s, the citizens who were left behind, often people of color of modest means, enjoyed few opportunities for advancement. Because state legislatures were frequently malapportioned and populated by amateurs with little interest in improving life for inner city residents, cities were mired in poverty, crime, and a rapidly deteriorating infrastructure.

Campbell addressed these crises in a series of publications arguing that the disparities between the affluent suburbs and more impoverished inner cities were growing wider. As a tragic result, poor urban residents were left in fiscally distressed cities with a dwindling tax base even as their need for government services increased. In his early work, Campbell implied that reform was needed, but it wasn’t until his later work that he set forth possible solutions. He believed that residents of affected communities should be involved in reform initiatives. Campbell also believed that city governments could be structured with two tiers that balanced regional concerns with community participation. In a series of books and articles, he explored the possibilities of initiating intergovernmental transfers to ensure the equitable distributions of federal funds. Campbell’s best-known books about these concepts included Taxes, Expenditures and Economic Base: Case of New York City (1974) and The Political Economy of State and Local Government Reform (1976).

He understood that the key to solving the problems of the inner city was to provide educational opportunities for children of poor urban families. The major obstacle to providing a quality education was the dearth of financial resources available to poor families. The disparity in resources between poor and affluent school systems ensured that the cycle of poverty visited on poor families continued across generations.

During the mid-1960s, Campbell was temporary member of the New York State Commission on the Revision and Simplification of the Constitution. Later, he served as a member of the Advisory Council on Continuing Higher Education. Owing to his expertise in metropolitan fiscal issues as well as his commitment to local government reform, Campbell was elected a delegate-at-large to the New York State Constitutional Convention. He was chairman of the Convention Committee on Home Rule and Local Government in 1967 as well as a member of the Herbert H. Lehman Fellowship Committee of the State Education Department in 1967 and 1968. During the early 1970s, he was a member of the New York State Council of Economic Advisors.

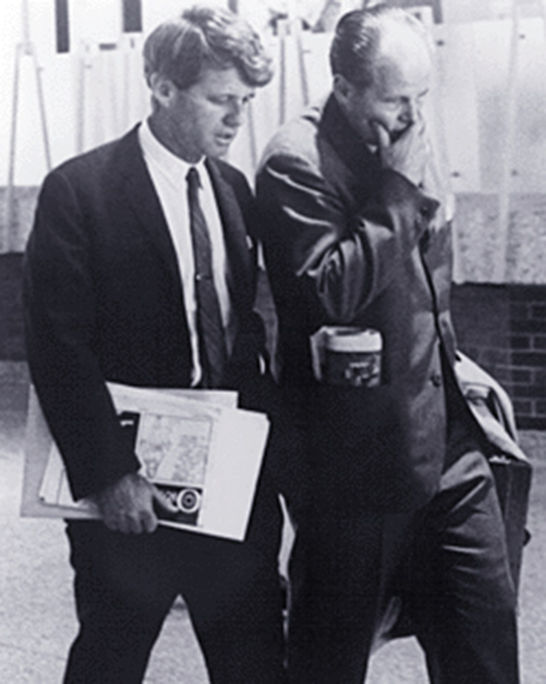

Although he conducted academic studies based on data and attempted to perform his government service in a bipartisanship manner, Campbell was a lifelong Democrat. He served as chairman of the New York State Democratic Platform Committee in 1962. From 1965 until 1968, he was a member of Senator Robert F. Kennedy's Military Academy Selection Board. Campbell’s commitment to reform and his passion for social justice dovetailed with Kennedy’s politically liberal policy prescriptions.

Campbell’s research on the need for educational equity culminated in his classic 1977 text, Financing Equal Educational Opportunity: Alternatives for State Finance. As a coauthor of this seminal study, Campbell used social science data to outline the funding disparities that plagued inner city schools. It was a book that reflected the authors’ academic expertise and their practical experience dealing with cities and their failing schools. In all his academic work, he insisted that the data should drive decision-making, and Financing Equal Educational Opportunity was no exception.

Campbell became President Carter’s point man for the Civil Service Reform Act (CSRA) of 1978. The need for civil service reform was evident. The federal civil service system was complex, expensive, and opaque, not to mention woefully antiquated. Assisted by many talented public administrators, including Jule Sugarman (founder of the Head Start program), and Dwight Ink, Campbell sought civil service reform to provide performance incentives and merit pay, allow for delegation of authority to the agency level, clarify labor management relations, and permit new research and development into federal human relations issues.

The sweeping new law revamped the federal bureaucracy, representing the first major reform since the Pendleton Act was enacted 95 years earlier. It divided the duties of the old Civil Service Commission into three separate offices: the OPM, the Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB), and the Federal Labor Relations Authority (FLRA). The law also created the Senior Executive Service (SES), a cadre of accomplished, experienced civil servants who moved between agencies applying cutting edge management techniques to complex government problems.

Following creation of the OPM, President Carter appointed Campbell its first director. According to the enabling statute, the OPM director’s principal responsibility is “in preparing such civil service rules as the President prescribes, and otherwise advising the President on actions which may be taken to promote an efficient civil service and a systematic application of the merit system principles, including recommending policies relating to the selection, promotion, transfer, performance, pay, conditions of service, tenure, and separation of employees.”

Although its functions are invisible to most citizens outside of federal service, OPM performs an essential duty. According to the agency’s reports, the “OPM serves as the chief human resources agency and personnel policy manager for the Federal Government. OPM provides human resources leadership and support to Federal agencies and helps the Federal workforce achieve their aspirations as they serve the American people. OPM directs human resources and employee management services, administers retirement benefits, manages healthcare and insurance programs, oversees merit-based and inclusive hiring into the civil service, and provides a secure employment process.”

Claudia Cooley, who later served as OPM’s associate director, remarked that Campbell’s tenure at the agency “woke up a complacent personnel community and shook up the federal workforce.” Campbell was constantly in motion, always studying OPM’s effectiveness and instituting reforms to improve its performance. He also urged the president to create the Presidential Management Fellows (PMF) program, a paid two-year fellowship at a U.S. government agency for American citizens with advanced degrees. The PMF program attracted thousands of talented young people to federal service, and it became a major pathway for entering public service.

Campbell served as OPM director for the last two years of the Carter presidency, finally departing when Ronald Reagan entered the White House in January 1981. Afterward, Campbell worked as the executive vice president of ARA Services before moving to the organization’s board of directors. He was elected ARA’s vice chairman in 1985.

Always restless, Campbell became a visiting executive professor at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania. He remained there before he retired in 1993. Even after retirement, he remained active on the board of the Maxwell School until his death. Moreover, Campbell was active in numerous professional associations, including the National Academy of Public Administration, the Institute of Public Administration, the Association for Public Policy Analysis, and the National Association of Schools of Public Affairs and Administration.

He received numerous honors during his career, including the Dwight Waldo Award for Contributions to the Literature of Public Administration, the Hubert H. Humphrey Public Service Award, the Common Cause Public Service Award, and the Gunnar & Alva Myrdal Award for Government Service. Whitman College, Syracuse University, and Ohio State University awarded him honorary doctorates.

Scotty Campbell died of emphysema on February 4, 1998. He was 74 years old. He left behind an unparalleled legacy of service in academe as well as in government.

Comments