The manuscript I have intermittently labored over for almost 18 years is titled Up From Clay. I chose the title to convey the idea that human beings have feet of clay, but they constantly strive to improve themselves, to move up from a debased condition toward something good and noble. It is a never-ending, ongoing, iterative process. Also, we are clay because we live and die. We rise from the earth, strut briefly on the stage of life, and return to the earth. Perhaps to some extent a human being can conquer death, or rise up from clay, by living a life of honesty and virtue.

As with many works of fiction, especially those penned by novice writers, the origins of the story are rooted in fact. I will discuss the novel itself — the plot, the characters, and the theme — in a future blog. For now, I want to talk about the facts behind the manuscript.

The facts are that I met a young guy named Will Morris in the fall of 1979. He had just turned 14. I was 16-years-old and entering my last year at Wilson High School in Florence, South Carolina. It should have been my junior year, but I had decided to graduate a year early. As a newly-minted high school “senior,” I was heavily involved in two things near and dear to me — the drama club, and myself (not necessarily in that order).

The drama club was good for me. It allowed me to come to terms with my shyness even if I never found a way to overcome it completely. I remain an incredibly shy person, and I struggle each day with this problem. Part of the reason my marriage dissolved was because I was too shy and weak to express my feelings to my wife. Yes, shyness is an ongoing problem, even at this late stage of my life (age 49).

The drama club helped me in this way: When I was 14-years-old and a freshman at Wilson, I appeared in my first high-school theatre production, Count Dracula. I cannot recall what possessed me to try out for the play, but I was thrilled to be cast as Heinrich Van Helsing, the vampire-hunting professor who killed Dracula.

Believe it or not, I still have a ticket from the 1977 production as well as a couple of photographs that someone gave me. (See the images, below.) The photographs were taken during the dress rehearsal. In the first image, I am pouring myself coffee during an early scene. In the second one, I am discussing a plot to kill Count Dracula with other characters. The young actors in the play became enormously important in my life. From left to right, they are Mike Lane, Ruthy Collins (seated), and Paul Bodie. That’s me on the end. They were older than I, and far more sophisticated — if anyone in high school can be called “sophisticated."

Ruthy later became the first serious girlfriend of my life. Nothing helps an adolescent boy handle shyness like having a girlfriend. For the first time in my life, a female (aside from my mother and my aunts) looked at me without revulsion. That is a boost for the male ego, believe me.

Count Dracula taught me that I need not be crippled by shyness. I could overcome. Wearing a fake mustache and spouting out lines written by a professional writer helped me to hide my insecurities behind a mask. Gradually, I learned how to stand in front of a crowd and spout out my own words without donning a mask. One must learn to walk before he runs, and Count Dracula figuratively showed me how to walk. (I have posted a couple of videos of myself giving speeches circa 2008 and 2009 on the “Events” tab of my website for anyone who wants to see how an almost unbearably shy person has managed to overcome this affliction. It takes a few minutes to load after you click onto “View Video,” so be patient.)

By the time I met Will Morris two years later, my cosmopolitan friends from Count Dracula had graduated from high school. I was the king of the Wilson High drama club in 1979-80. Normally, as the self-anointed king, I would not have noticed a freshman like Will Morris. Three things changed the normal course of events. First, he tried out for a one-act play, No Why, and captured a part. I was the lead character, “Father,” and Will played my son, a Christ-like character. Second, Will had a wicked sense of humor that matched my own. He was not intimidated by me in the least, and he never hesitated to blurt out the weirdest, rudest, most hilarious comments I had heard. Third, he could play a mean guitar, and he possessed a passable singing voice.

As is true with many adolescents, music played an important role in my life. Although I came of age at the end of the 1970s, I was mired in the music from a decade earlier. Eschewing disco and the dance tunes of my era, I immersed myself in music from the Beatles, Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones, the Who, CCR, and the Doors. Unfortunately for me, I have no musical ability whatsoever. Thus, I admired people who could sing and play songs. Will was one of those people.

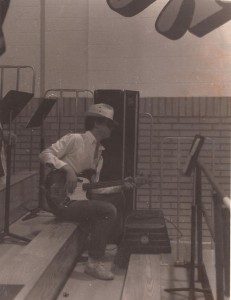

Here is a photo of Will playing the bass at Socastee High School near Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, sometime in the early 1980s. I thought he was one cool customer in those days.

We became fast friends during my last year of high school. I remember a great deal from those days, especially the trips we took with the drama club. Our high school drama coach, Rupert Gaddy, entered us in drama competitions throughout South Carolina. My favorite trip was a visit to Charleston late in 1979. We stayed in the Francis Marion Hotel. One afternoon, Will and I wandered up to the roof — a dangerous activity for two teenage boys, but that was what made it so exciting. I will never forget that day. I have written about it several times in draft stories. I changed Will’s name to Wake (for reasons I will explain in a future blog) as well as the name of the hotel, but here is how I described the scene in Up From Clay:

During my senior year, Wake and I performed in the Beauregard’s grand ballroom in a one-act play called No Why at a drama competition sponsored by the Hortense Community College Players. The play was a masterpiece of teenage existential angst, and we snagged third place in the Most Pretentious Drama category. Wake appeared as a Christ figure and I played the part of the Pontius Pilate stand-in.

Following the performance, while other actors and stagehands tore down the set and loaded the van, Wake and I slipped away. We found a staircase and, much to our delight, discovered that it led up six stories to the top of the hotel. The door was unlocked, so we climbed up onto the gravel and tar roof.

For fun, we spit down onto passing cars and trucks. We grew bored with this activity after several minutes, so we searched the roof for more pleasant diversions. Wake found a color wheel, a book of small, rectangular gels used for coordinating wallpaper and fabric colors. We didn’t know how it got onto the roof, but there it was. Naturally, he and I felt compelled to tear off pieces and toss them over the side.

Wake ran downstairs and stood next to the road as I tore off swatches one-by-one and threw them down to him. They floated on the breeze like umbrellas or parachutes. Every now and then, one landed on top of a passing car or in the bed of a speeding pickup truck.

We changed places. He stood on the building and I guarded the road, squinting up through the sunlight to watch the gels float down. I lunged after a few as they fell, but I was afraid I might hurl myself into oncoming traffic, so I stopped and looked up at Wake and the gels from a stationary position on the sidewalk.

I will never forget that moment. My brain took a snapshot and stored it away. To be young and full of promise on a sunny day when the world’s horizons seem limitless is not something to forget. Whenever I feel sad or depressed, worried about the sorry state of my life, or disappointed in the man I have become, I think of those gels, the rooftop of the Beauregard Hotel, and my enduring friendship with Wakefield Wilkerson. That was a time before Nell came into the picture, when everything was pure and uncomplicated, when all we had to worry about was our lines in a play and the aerodynamics of swatches from a color wheel.

Although much of the book is the product of my imagination, that scene is exactly as I remember it except for the name changes.

I graduated from Wilson High School on May 30, 1980. That fall, I left Florence to attend Furman University in Greenville, South Carolina, 180 miles away. Will and his family moved from the Quinby community in Florence to Murrells Inlet, South Carolina, in the summer of 1980. Our Florence connection was severed, although we stayed in touch. We visited each other during the summers.

One of our more memorable visits came on August 7-8, 1983. Will had just graduated from high school and he was less than two weeks away from his 18th birthday. I was 20-years-old and preparing to enter my senior year at Furman. Will came to my boyhood home in Florence and spent the night. He brought several guitars, a banjo, a bass, a synthesizer, and a microphone with him. Despite my lack of musical ability, I enjoyed writing songs and playing around with my musically-gifted friends. (I wrote lyrics while friends such as Will came up with the music.)

After we wrote a few tunes, we wanted to record a familiar song. Will and I were both Rolling Stones fans. I was delighted to find that he had mastered the chords to one of our favorite Stones’ songs, “Dead Flowers.” We decided to record our version of the song on the evening of August 7. As we were rehearsing in my bedroom, surrounded by posters of my favorite rock bands, my mother appeared in the doorway with camera in hand. She was never much of a photographer, so we were not centered in the resultant photograph. Still, mom managed to capture an image of two young men enjoying a magical moment in their youth. I looked up just as she snapped the photograph, but otherwise we were participating in an unguarded, exuberant experience.

I look at those faces and smile. Almost three decades have passed since that image was captured on film. I have lost most of that hair. I now wear glasses and struggle to keep my weight under control. I have been beaten down by life. I have given up on conquering the world. Still, I like to think that I have fulfilled some of the promise I exhibited in those days — not musically, of course, but in pursuing my creative writing dreams.

Will, however, is dead.

Even now, after all these years, it hurts to write those words. Will is dead. I have come to accept it, but I will never understand it.

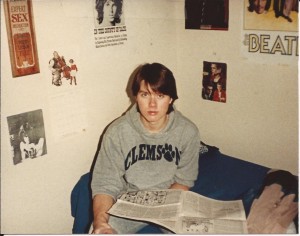

He came to see me several times during my years at Furman. In February 1984, he was a student at nearby Clemson University. One Saturday morning, he drove over to my dorm room and we visited awhile. I took this photograph of him sitting on my bed reading an editorial I had written for the school newspaper.

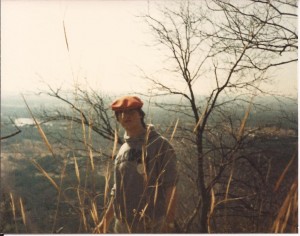

Later that day, Will and I hiked around Paris Mountain near the Furman campus. I captured this image of him on the mountain. It is grainy and faded. The photograph has a long-ago feel to it, which makes sense; it is a long-ago time. The Furman University Lake is visible in the background in the left of the photograph.

I graduated from Furman on June 2, 1984, and went off to law school at Emory University in Atlanta. Will came with me to sightsee around Atlanta in March 1984 when I attended the Emory visiting day. After that trip, we gradually lost touch. We would write to each other or speak on the telephone from time to time, but the years have a way of dissolving even close friendships.

Fast forward almost a decade. I was living and working in Norcross, Georgia, an Atlanta suburb, when Will’s sister, Emily, called me out of the blue on the evening of January 13, 1993. I had not spoken with Will or Emily in many years when I picked up the telephone. As soon as I heard her voice, I knew something was wrong.

I described the phone call in the opening pages of Up From Clay, although I changed the facts a bit. The town of Florence became the fictional “Hortense.” The three dogs mentioned in the book are the dogs I have now. The Nell character, which I referenced in the earlier excerpt, was completely made up. Will Morris died, I believe, from an aneurysm, but I changed that fact in Up From Clay to suit a later plot development. Still, this passage captures much of the shock I felt during the 1993 telephone call:

Death comes into my home on Wednesday evening after dinner. I am scraping the last morsel from the can when the shrill ringtone jolts me from my daze. As usual, the hounds start baying while I pull the receiver to my face. They are wonderful watchdogs, harbingers of the obvious.

“Dammit, guys.” I lean down and slide my plate across the linoleum. They lunge at the unexpected booty, with Choctaw beating the others to the punch. I watch his big pink tongue furiously slap through the gravy before the others can share the wealth. As my mother would say, he is a greedy gut.

“Sorry about that,” I tell my caller.

“Hey, Mike. It’s Emily.”

“Emily? Emily Wilkerson? Really?”

Holy Christ. I haven’t spoken to Emily in — how many years?

As I struggle to calculate the figure in my head, she reads my thoughts. “It’s been almost seven years. How have you been?”

How have I been? I hate that question posed by someone who has slipped from my life. How have I been during the past seven years? I have been up and down. What do you think? How have you been?

“I’m okay, Em.” My words say one thing, but my tone conveys unease and curiosity.

She must sense my confusion. “You’re probably wondering why I’m calling out of the blue. It’s about Wake.”

Uh-oh. Something in her voice sounds ominous. This is not a convivial invitation to stroll down memory lane. Whatever reminiscing we do will occur along a dark, sad road.

“Mike, he died this morning.”

What? I feel as if I have been punched in the stomach. Someone rips open the airplane door at 30,000 feet; the air is sucked from the room. I moan. The world spins, flip-flopping on its axis, becoming a wild vertigo roller-coaster ride that might end with me crashing to the floor if I don’t plant my ass in a chair.

I open my mouth to speak, but nothing emerges. Thank God I hold a cordless phone or it might fly from my hand as I stagger into the kitchen. Mister Buster emits an indignant yelp when I step on his tail. I collapse onto a stool.

“Are you still there?”

“What — what happened?” My voice sounds tinny and hollow, a croak emanating from a tin can tied to a string. I am conscious of my heartbeat pulsing in my ears.

“They think it was anaphylactic shock. Similar to what killed Bruce Lee.”

“Shock? Like an allergy?”

“Yeah.”

“Was he stung by a bee or something?”

“We don’t know what caused it.”

The dogs growl at each other. The gravy long gone, they jockey for position to lick the plate beyond spotless. I kneel, retrieve the dish, and place it on the table.

“Oh, my God, Em. I don’t know what to say.”

“There’s nothing to say.” I hear convulsive sobs shoot through 800 miles of telephone line. She struggles to speak again, and fails.

Silence envelopes us like a sacred death shroud.

When she can speak again, Emily clears her throat. “We’re still making plans, but the funeral will be on Saturday at 3:00 in daddy’s church. In case you want to come.”

In case I want to come. She knows how little I desire to visit the ghosts of my hometown. We have lost touch, but we still know each other, Emily and I.

“Yes. Of course I’ll come.”

“The family will receive guests on Saturday from 11 until one at the Weeks Funeral Home. You know where that is? It’s sorta new. Near Skeeters — not far from Kwikley’s.”

“Yeah. I think I know where it is.”

“Nothing much moves in Hortense. Nothing much changes.”

I utter the obligatory guffaw. “That’s for sure.”

We suffer through another bout of silence.

I finally cough. “How are you holding up? How’re your folks?”

“You really want to ask about Nell.” Even after all these years, I can tell when Emily is petulant. She is petulant now.

“I want to know how you’re all doing.”

“We’re still in shock, numb. We’re calling friends to tell them the news.”

I lean my elbows on my knees. “The news. It’s just so…unbelievable.”

“Nell asked about you. She said she would call, but I wanted to do it.”

“Yes, well. Thank you for that.”

“It’s been a long time, Mike. The folks would love to see you.”

I sigh. “I don’t know about that.”

We fall silent again. When Wake and I appeared in high school theatre productions, our drama coach, Mr. Gaddy, always screamed at us to pick up our cues. Emily and I do not pick up our cues.

Finally, she speaks. “So I’ll tell the folks you’re coming?”

“Sure. Sure.”

“See you on Saturday.”

“See you, Em.”

The phone line dies, and part of me dies, too.

Wake is dead. I cannot wrap my mind around that concept. I cannot envision a world without him. I am his senior, and already he is bound for the grave.

Daisy touches her cold nose to my leg, reminding me of my earthly duties. My dogs cannot subsist on leftover gravy. They must be fed. The garbage smells bad, and must be tossed to the curb. I must post final grades or my students and the registrar will hound me to no end.

My childhood friend lies dead in my hometown, and still the world goes on.

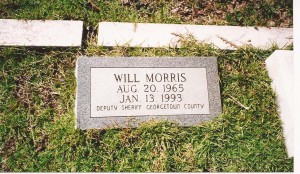

I attended the real Will Morris’s funeral. It was indescribably sad. What kind of a world do we live in where a 27-year-old man drops dead from natural causes? He was a deputy sheriff at the time, and I thought he might have died in the line of duty. Yet his death was far more prosaic. It was just one of those things.

I wrote this dedication to my first book, Life and Death in Civil War Prisons (2004): “This work is dedicated to the late Will Morris (1965-93) who scribbled in my high school annual all those years ago that we would be ‘friends forever.’ He was right. Death takes only what must be surrendered.”

I have been thinking a lot about Will lately because I am revising Up From Clay and because I read his father’s obituary in 2011.

http://www.legacy.com/obituaries/myrtlebeachonline/obituary.aspx?n=w-robert-morris&pid=148689542

A few faded photographs and cherished memories are all I have left of my friend. Yet I will always honor him. He no longer lives in this world, but he will always live in my heart. Perhaps one day, an alternate version of him will live in the pages of my fiction.

Save